For startups, “getting to scale” means translating a small idea into a broader application in order to create increased influence, effectiveness, and growth. Communities around the world are seeing a similar push, with sustainability concepts that have flourished at the building scale for over two decades now finding their way into urban design and planning. One specific concept many have grasped to apply sustainability at the community scale are “ecodistricts,” which have become a way to expand the reach of green building-based solutions to address equity, energy, water, food, and mobility concerns at the neighborhood level, where results depend on the exchange of resources “at scale” – and outside the property line.

Ecodistricts have much in common with traditional urban design and planning, but differ because they respond to the relationship of resource flows within the urban framework. There are three major shifts in our urban context that distinguish ecodistrict planning from other planning models: 1) the need for infrastructure renewal and integration into urban spaces, 2) the possibility of adaptive response to resource flows and climate change, and 3) the emerging demand for a new way of community participation.

Integrating Infrastructure into Urban Design

First, ecodistricts create new ways to integrate infrastructure into our urban places – bridging the gap between large, one-way, source-to-user systems (such as a regional power plant) and the performance or maintenance limitations of parcel-based systems (like building-mounted solar panels). This middle scale of distributed, decentralized infrastructure has the potential to create new urban experiences, essentially places that showcase shared infrastructure such as energy hubs, rainwater parks, or other systems that effectively manage local resources.

Initiated in 2014, the Uptown EcoInnovation District is Pittsburgh’s newest ecodistrict, with immediate plans to become home to a microgrid and energy generation plant that will provide electricity, heating, and cooling to UPMC’s Mercy Hospital and other nearby buildings and businesses. The project helps meet existing demand with nimble systems suited to local requirements and the district energy building itself will visibly showcase these systems.

Ecodistricts provide the planning frameworks to imagine and implement innovative infrastructure systems, while developing equitable relationships between institutional, commercial, and residential stakeholders. Uptown is in the middle of a year-long community-informed process that examines how infrastructure investments in transportation, stormwater, and energy (including the microgrid) can benefit all stakeholders in the community.

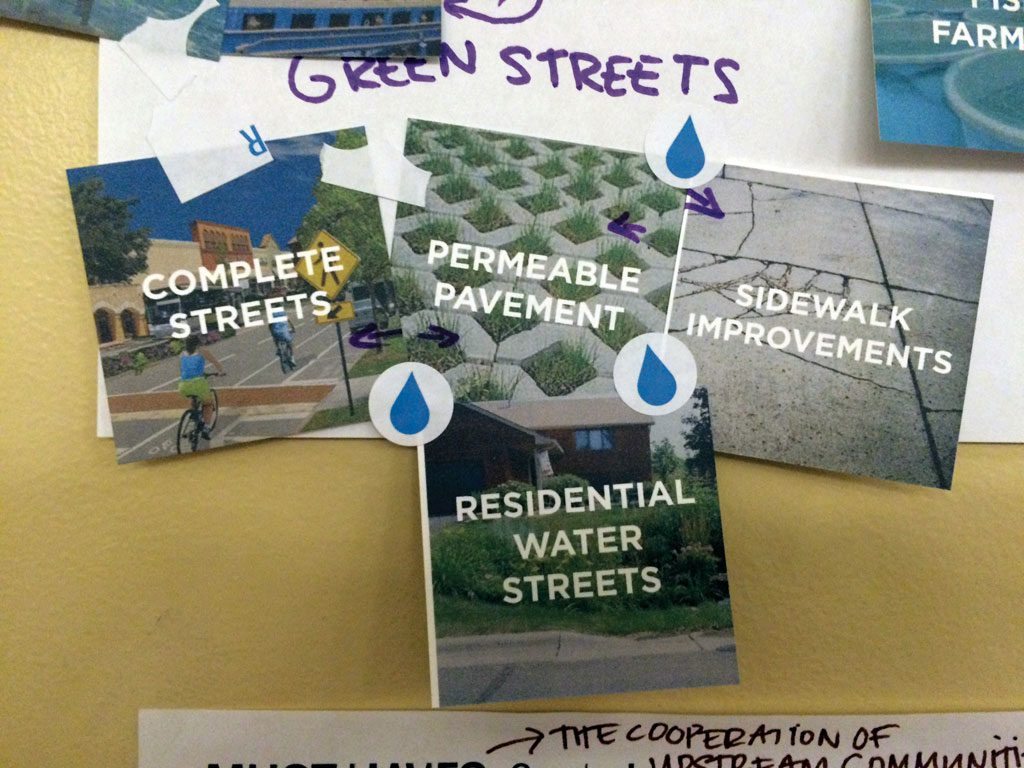

Millvale community members select desirable types of projects from a strategies deck. Photo credit: evolveEA

Adaptive Response to Climate Change

Ecodistricts also provide a way for communities to measure and respond to climate change as more volatile hyper-local environmental conditions are experienced. Fortunately, new technologies better enable measurement and monitoring of those changes, allowing communities to develop appropriate responses to react and adapt.

Just north of Pittsburgh, the community of Millvale recently completed its second round of ecodistrict planning, “Pivot 2.0.” While Millvale’s 2013 Pivot 1.0 focused on water, food, and energy, Pivot 2.0 additionally addressed new topics of mobility, equity, and air quality. Both plans started with benchmarking efforts to measure current district performance and understand how future models of climate change might affect residents and businesses.

Millvale began by identifying resident health as an issue of concern since its rate of cancer and other lung-related diseases are much higher than regional averages. As such, Millvale residents are especially susceptible to excessive heat, moisture, and other conditions associated with climate change. Local leaders are currently measuring air quality throughout the community to better understand how concepts such as air quality zoning and clean air parks might provide new community amenities, while improving the borough’s health statistics. Some of the actions (like improving building envelopes) will be done by homeowners. Other actions (such as air quality buffer zoning) can be done at the municipal scale. Still others will require regional changes, for which the community will be a vocal supporter. Millvale’s ecodistrict plan helps identify actions that residents can take in the short term, while advocating for longer term improvements.

“Having felt the negative impacts of past industrial and developmental practices, the community wanted to transform itself in a way that would carry Millvale into the 21st century,” said Zaheen Hussain, Millvale Borough’s sustainability coordinator. “As a planning process, EcoDistricts allowed involved residents and community leaders to rally around a shared vision that they all had a hand in creating.”

Community Participation Reinvigorated

Ecodistrict planning builds a sense of community and helps define issues of equity by encouraging community ownership in the creation of high performing community places. Successful communities have effective decision-making processes, are good at learning and sharing knowledge, have legal ability to take action, and can harness financial resources to turn their vision into reality. Ecodistrict planning is not a one-time transactional effort, but an ongoing, transformational relationship with a community that pays attention to the “software” of social systems as much as the “hardware” of physical systems.

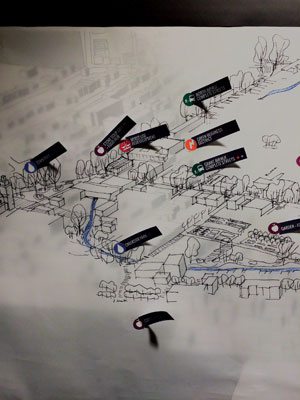

Community members map green infrastructure in a session for the Living Waters of Larimer project. Photo credit: Living Waters of Larimer

Pittsburgh’s Larimer neighborhood undertook the region’s first ecodistrict planning process in 2011 — and the community has been highly successful at harnessing development pressures to meet their sustainability goals. Larimer’s extremely dedicated residents have a high level of knowledge about stormwater, building performance, energy, and environmental justice. Through partnerships with public agencies, nonprofits, and projects, the residents have continuously advanced their sustainability values over the past five years, managing to secure over $50 million for projects that contribute toward ecodistrict goals.

One specific area where Larimer’s active and sustainability-conscious citizen base has had great success is securing investment for green stormwater infrastructure. Both nonprofit and for-profit projects in the neighborhood demonstrate the viability of green infrastructure, with two very visible installations influenced by the community’s commitment to sustainability: the Environment and Energy Community Outreach (EECO) Center gardens and Bakery Square 2.0’s low-impact development. Recently, Living Waters of Larimer, a community-based arts project, helped envision Little Negley Run as the city’s first rainwater park, as well as a neighborhood gathering space, The Well, focused on water. Little Negley Run is currently being engineered and The Well is about to commence work with local artists to create a park installation. Both projects will ensure that Larimer continues to be on the cutting edge of shared rainwater infrastructure.

The Pittsburgh-area neighborhoods of Larimer, Millville, and Uptown represent but a few of the local community-scaled sustainability efforts in Western Pennsylvania. All three have been applying ecodistrict planning as a means to create project frameworks that “get to scale,” while helping to share successes and challenges across geographic and neighborhood boundaries. As existing projects are implemented and new communities developed, the next several years will continue to launch Pittsburgh into the national ecodistrict spotlight. Stay tuned for future updates from these places and many others as ecodistrict communities work individually and collaboratively to create more sustainable, equitable places for all!

About the author

Christine Mondor

Christine has been shaping places, processes and organizations nationally and internationally through her work as an architect, educator, and activist. Christine leads the urban design and planning practice at evolveEA where she helps communities envision urban regeneration strategies. Her projects integrate urban infrastructure with creative placemaking and are known for their rigorous yet engaging design processes that build community capacity. Recent projects such as the Centre Avenue Corridor Redevelopment Strategy and the Millvale Ecodistrict plan have been recognized by various organizations including the American Institute of Architects and the American Planning Association at the local, state, and national levels.

Christine teaches architecture, landscape design and sustainability at Carnegie Mellon University. She supports organizations that promote design and the environment and currently serves as Chair of the Pittsburgh Planning Commission, President for the Green Building Alliance Board of Directors, and is a member of the Global Ecodistricts Protocol Advisory Committee.

This article was originally published in Viride, a new publication of the Green Building Alliance. PRISM extends its gratitude to Viride and the GBA for sharing this article with PRISM’s readers.

About Viride

The annual publication showcases the projects, people, and perspectives that are leading our region’s innovative green building industry.

In Latin, “viride” (pronounced vĭrĭdā or VEER-uh-day) means fresh, green, blooming, and youthful. At Green Building Alliance, as we strive to advance healthy, high performing, and green buildings and places that are environmentally responsible, socially just, and economically viable. Thus, naming our annual magazine Viride seemed like a good way to designate how we and our many stakeholders work with passion, enthusiasm, and goals that help our region grow. Though GBA is approaching our silver anniversary as an organization, we still feel youthful and excited by the green building and sustainable placemaking projects and potential the future holds – and we are proud to have been helping regional and national leaders and partners water the seeds of sustainability we’ve been planting together for the past 23 years.